For the first time, we know what Tyrannosaur faces really looked like

Tags: Montana

For the first time, we know what Tyrannosaur faces really looked like published by nherting

Writer Rating: 0

Posted on 2017-03-30

Writer Description: current events

This writer has written 195 articles.

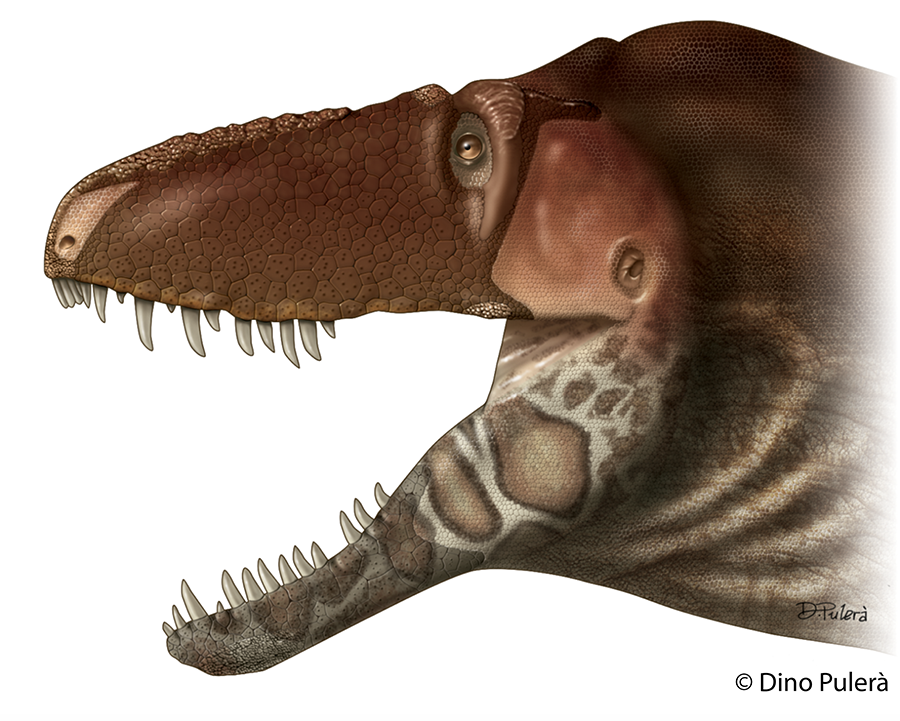

New scientific discoveries about Tyrannosaurs have upended our understanding of the giant predators whose massive populations extended from Asia to the Americas. They had feathers. They ran like birds. And now, a new species that lived approximately 100 to 66 million years ago in Montana has given us our first real look at these dinosaurs' faces.

Carthage College paleontologist Thomas Carr and his team describe the scaly visage of Daspletosaurus horneri in a new paper from Scientific Reports. A typical member of this species would have been about nine meters long and 2.2 meters tall, with its large skull covered in bony ridges and different skin types. The researchers write that D. horneri is "critical to understanding the evolutionary transition from nonbeak to beak along the line to birds, since beaks are specialized epidermal structures." In other words, it's not just badass to reconstruct what a tyrannosaur's face looked like—it also gives us a glimpse of the in-between stages as snouts evolved into beaks.

By carefully examining the textures on different parts of a well-preserved skull of a D. horneri, the researchers were able to reconstruct what kinds of tissues and systems of nerves would have covered them. Their work was helped in part by a massive database of tyrannosaur bones, which they could use for comparison, ruling out textures that might have been created by damage during fossilization. Once they were certain these textures were created by tissues attached to the skull, the team compared the skull to those of modern birds and crocodiles, whose facial bones show nearly identical patterns.

Immediately, they found that the tyrannosaur's lower jaw showed evidence of having "neurovasculature that is also seen in birds." Specifically, it seems that D. horneri had a trigeminal nerve, an ancient piece of anatomy found in many animals whose faces are highly sensitive to vibration, infrared radiation, electricity, and even magnetic fields. Louisiana State University researcher Jayc Sedlmayr, who worked on the paper, told the Guardian that this nerve "has an evolutionary history of developing into wildly different 'sixth senses' in different animals."

In some creatures, whiskers provide sensory input to the trigeminal nerve. But in D. horneri, this nerve would have been connected to highly sensitive flat scales on the tyrannosaur's nose and around its mouth. Each of these scales would have been packed with nerves, acting as what biologists call integumentary sensory organs (ISOs). These nerves, write the scientists, were so dense that they could transmit "high resolution tactile sensations from the skin, making their snouts more sensitive than human fingertips."

Today's crocodiles also have scaly ISOs on their faces, which makes sense because crocs share a common ancestor with tyrannosaurs. Crocodiles mostly use these sensors to detect small vibrations in the water to locate prey, but it's unlikely that tyrannosaurs hunted much in the water. Still, Carr and his colleagues believe that other types of crocodile behavior offer clues about how D. horneri used its sensitive scales. As they write:

As in crocodylians, female tyrannosaurids would have relied upon ISOs on the snout for detecting the optimal temperature of a nest site, and for maintaining nest temperature and the nest materials; also, ISOs would have aided adult tyrannosaurids in harmlessly picking up eggs and nestlings and, in courtship, tyrannosaurids might have rubbed their sensitive faces together as a vital part of pre-copulatory play.

Yep, tyrannosaurs were probably rubbing their faces together to stimulate those nerve endings before sex. We've discovered the secret of megafauna foreplay.

But what, exactly, would you see if you looked a tyrannosaur in the face? Given that they had so many sensitive scales, it's extremely unlikely they would have sported feathers. There would have been many flat scales around their noses and mouths and harder plates covering the regions around the back of their jaw and neck. D. horneri in particular had a lot of ridges above and behind its eyes, made from the same material as human fingernails or goat horns.

Basically, we're talking about a giant, crocodile-faced chicken at this point. And it would have rubbed faces with other giant, crocodile-faced chickens before having sex. Just try to get that image out of your mind.

Sources: https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/03/new-discovery-reveals-tyrannosaur-faces-for-the-first-time/

You have the right to stay anonymous in your comments, share at your own discretion.