A Scientific Guide to the Fantastical Predators in Game of Thrones

Tags: USA

A Scientific Guide to the Fantastical Predators in Game of Thrones published by Evanvinh

Writer Rating: 5.0000

Posted on 2016-04-23

Writer Description: Evanvinh

This writer has written 733 articles.

The monsters in George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones are magically badass. But are dragons, direwolves, and lizard-lions scientifically plausible on some level? Today we’re going to try to answer that question—with the help of some expert biologists.

We’ll explore the hypothetical anatomy, ecology, and behavior of the iconic fantasy creatures of Westeros and Essos, and try to draw conclusions about whether any of these beasts could exist in our boring, non-magical world.

Dragons

Dragons—massive, flying, carnivorous reptiles with no natural predators—are arguably the most iconic fantasy beasts of the Game of Thrones series. They possess an awesome and terrible power, the ability to lay waste to armies and cities alike with their fiery breath.

Thousands of years before the events of the Game of Thrones series, dragons of were discovered lairing in the Fourteen Flames, a large volcanic chain that extends across the Valyrian peninsula. It was the sheep-herding folk of Valyria who first learned to tame dragons, eventually using the beasts to forge a vast empire across the continent of Essos.

“Old Valyria.” Image Credit: Ted Nasmith

Centuries later, an apocalyptic volcanic eruption killed most of the world’s dragons and ended the Valyrian empire. The species was thought to be extinct until Danaerys Targaryen’s dragons hatched at the beginning of the series.

When dragons vanished from the world, knowledge of their biology was lost, so we’ll have to fill in the gaps with comparative anatomy and a healthy dose of wild speculation.

Could a dragon actually fly?

The dragons of Game of Thrones have long, sinuous bodies with snake-like tails, short back legs, and large front wings similar to those of a bat. They’re got a thick layer of scaly black armor, which probably offers protection against the occasional molten magma shower.

It’s unclear just how big the dragons of ancient times got. But like many reptiles, dragons never stop growing, and they lived upwards of two centuries. If the truck-sized skull Arya discovers in the dungeons of King’s Landing is any indicator, the dragons of ancient Valyria were larger than any animals that ever took to the skies on Earth.

Which brings us to the big science question: could a creature this large actually become airborne? To find out, I spoke with paleontologist Mark Witton, an expert on the largest animals that ever flew—pterosaurs.

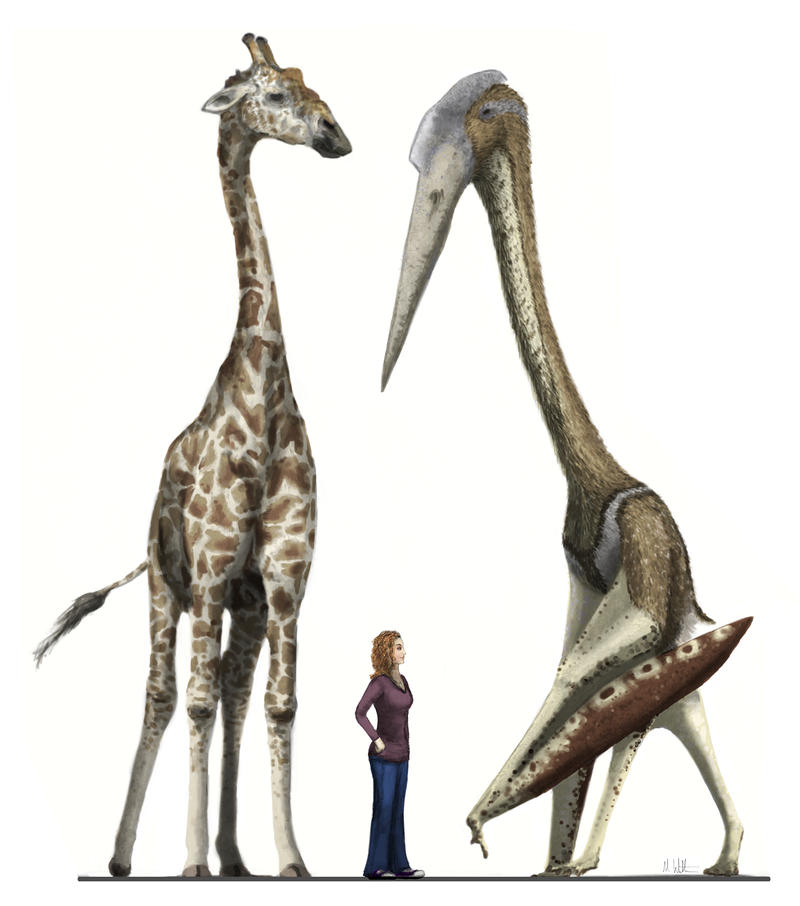

Pterosaurs were bird-like, carnivorous reptiles that lived from the late Triassic through the Cretaceous. The largest known pterosaurs, the azhdarchids, died out 66 million years ago, in the same mass extinction event that killed the dinosaurs. Based on the fossil record, azhdarchids achieved wingspans of over 30 feet and weighed upwards of 500 pounds.

The giant pterosaur, Arambourgiania, compared for size against a giraffe and a human. Image: Mark Witton

How did such a large animal get itself off the ground? First and foremost, pterosaurs needed to be as light as physically possible. Their bones were hollow, and in some cases extremely thin. For additional buoyancy, pterosaurs had large air sacs dispersed around their muscles and throughout their body.

“These adaptations were critical,” Witton said. “While a giraffe may weigh a ton or two, a pterosaur of the same size would only weigh as much as a large pig. For dragons to be flight-worthy, they’d almost certainly have to have hollow bones, as well.”

The meat that a pterosaur did put on was carefully distributed.“The biggest pterosaurs were essentially a fairly small body wrapped in loads of concentrated muscle,” Witton said. “As you move away from the animal’s core, their limbs become spindly very quickly.”

Turns out, that’s not too different from the body plan we see in the Game of Thrones dragons. “What’s really cool about the dragons in Game of Thrones is they’ve got these big, deep chests, and as you move away from the body, the wings and arms get proportionally quite thin,” Witton said. “That’s actually pretty accurate. If I were designing a dragon for flight, I’d go for a similar body plan.”

The big thing weighing Daenerys’s dragons down is their tails. “We know that early pterosaurs had fairly long tails,” said Witton. “But they were very slender and whiplike. When I look at that dragon tail, that looks more like something a croc would possess, which is fine for ground movement, but probably a bit too massive for flight.”

To get a hefty tail off the ground, a dragon would need to expend precious energy. Which brings us to another major point of consideration: to sustain its active, rampaging lifestyle, a dragon is going to need a lot of calories.

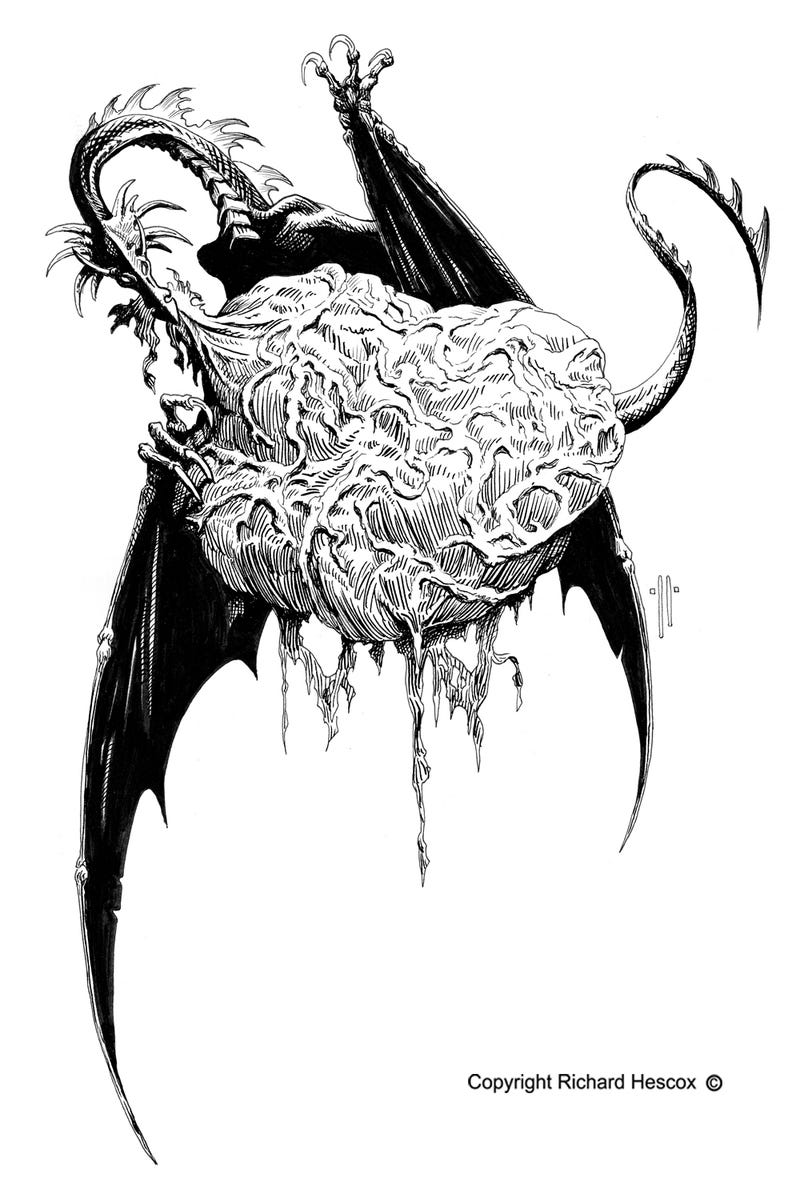

Image: Richard Hescox. Find more of his art on Facebook.

Fortunately, we know that dragons aren’t picky eaters, and that slaying an entire village is about as challenging as microwaving a hot pocket. But how many calories would a dragon have to eat to spend all day pillaging from the air?

I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation to find out. According tofreedieting.com, a six foot tall, 200 pound man who works a physical labor job needs to consume 3600 calories a day to maintain his weight. Let’s just assume this man’s lifestyle and physiology are comparable to that of a dragon’s. In that case a one ton, adolescent dragon would need to consume 36,000 calories a day.

According to Calorie King, a pound of beef flank contains approximately 880 calories. So, our mid-sized dragon would need to eat 41 pounds of steak a day to maintain its weight. Which doesn’t actually sound too crazy. If we’re conservative and double that amount, a single human meal could still feed a dragon for several days.

But would a dragon’s post-lunch food-baby bog it down for the rest of the afternoon? Maybe. “Some scavenging birds gorge themselves and struggle to take off afterwards,” Witton said. “Pterosaurs too might have gotten themselves into situations where they needed to work that food through before takeoff.”

A group of giant azhdarchids foraging on a Cretaceous fern prairie, one with a juvenile titanosaur in its beak. Image: Mark Witton.

Still, Witton said, based on the mechanical stress their bones can handle, it’s conceivable that 500-pound pterosaurs flew after eating 80-pound meals, albeit with difficulty. Which puts a dragon eating a human and continuing on its merry way within the realm of physically possible.

And lest we forget, dragons have one ability that’s giving them a big leg up when it comes to energy: fire. “You need to be warm bodied to fly,” Witton said. “If you’re an insect, you power up in the sun, if you’re a bird or a bat, you generate your own heat and use a furry coat to keep yourself insulated. We assume pterosaurs were similar to birds and mammals in this respect.”

For non-magical beings, maintaining core heat means burning calories. But if we allow dragons this one otherworldly skill, the animals have a self-replenishing heat source at no additional cost. “It would certainly help solve the problem of food,” Witton said. “If there’s a way they can keep warm without burning extra calories, it’s possible dragons could have proportionally lower caloric intake than a bird or a mammal.”

Who knows—maybe breathing fire frees up enough energy to make that hefty tail manageable.

A predator to rule the world

As massive carnivores with no natural enemies, dragons are almost certainly the apex predators in their environment. Which might be the entire Game of Thrones world, if we again look to pterosaurs—whose fossils are found nearly everywhere on Earth—for comparison.

Image: Aggiorna, via Wikimedia Commons

“A giant pterosaur could take off from England, fly over the Eastern US, most of the way inland, and back to the UK in a single journey,” Witton told me. “Now, that would be an extreme flight, and it would be very thin afterwards, but the fact is, we’re talking animals that could cover thousands of miles, at top speeds of close to a hundred miles per hour.”

“If you translate that to Game of Thrones dragons, you’ve got to assume they could have hunted all over Westeros,” he continued. “The narrow sea is an afternoon trip, and as they get bigger they’re just going to be moving faster.”

Many apex predators on Earth today also cover enormous ranges. Take theSiberian tiger, whose hunting grounds span hundreds of miles, or the great white shark, which can swim from South Africa to Australia and back in a year. Rare as these hunters may be, they can have a profound influence on their environment, by keeping smaller populations of carnivores and herbivores in check.

As larger and more destructive apex predators than anything on Earth, we can almost view dragon attacks as a natural disaster—one that hammers ecosystems when it hits, but occurs so rarely that populations have time to recover between attacks. We’ve got no way of knowing how different things were when dragons ruled the skies of Westeros and Essos, but given their size, range, and sheer might, it seems fair to assume they were the dominant ecological force the world over.

Direwolves

Ghost, Jon Snow’s direwolf companion.

The Direwolf, sigil of House Stark, may be a more loyal companion than a dragon, but it’s an equally vicious killer. Direwolves once claimed a vast swath of the North as their home, before hunters drove them away. Today, they still roam the forests and tundra lands north of The Wall, and are occasionally spotted by men of the Night’s Watch. Direwolves are social, hierarchical pack hunters, but if adopted at a young age, they can become fiercely devoted to a human master.

Is a direwolf a dire wolf?

Unlike dragons, direwolves seem to be directly inspired by a once-living creature. The dire wolf, Canus dirus, was a top predator across most of North and South America during the Pleistocene, until it disappeared along with many of our planet’s megafauna some 12,000 years ago. To find out how George R.R. Martin’s direwolf compares to its Earthly counterpart, I spoke with Robert Dundas, a paleoecologist who has been studying the creatures for decades.

There were some striking differences.

Image: Richard Hescox. Find more of his art on Facebook.

Direwolves in Game of Thrones are basically a jacked-up version of gray wolves, with several key anatomical differences. They’ve got larger heads, a leaner, more pronounced muzzle, longer legs in proportion to their bodies, and large, razor sharp teeth. An adult direwolf can get as big as a small horse.

When I described the Westerosian direwolf to Dundas, he started to laugh. “People have this image of dire wolves as being these massive creatures,” he said. “But in terms of overall body size and proportions, they’re actually pretty similar to a timber wolf or gray wolf.”

The key anatomical difference, Dundas said, has to do with bulk rather than size. “When you reconstruct the dire wolf’s musculature based on its bone structure, you end up with a much huskier wolf,” he said. What’s more, dire wolves of the Pleistocene had slightly shorter limbs than gray wolves, making their bodies less suited for high-speed chases.

But don’t let size fool you: the hunting skills of Pleistocene dire wolves are legendary. In packs, these animals could tackle some of the largest prey around, including giant North American ground sloths, camels, horses, and perhaps even young mammoths. In South America, they ate an entirely different set of large herbivores. Which brings us to another difference between the Stark childrens’ direwolves and the Pleistocene variety: their habitat.

“Dire wolves lived in a wide range of environments,” Dundas said. “We find them in open grasslands, closed forests, and from sea level up to 8 thousand feet in elevation or more.” The only place dire wolves didn’t live? The far north. The northernmost fossil evidence for dire wolves hails from southern Alberta, roughly coinciding with the edge of the Laurentide ice sheet.

“There is no evidence that dire wolves existed in glacial environments,” Dundas said.“We’re not really sure what to make of this northern range limitation, given that they’re pretty well-adapted to live in just about any sort of environment.”

A pack of gray wolves on a snowy landscape. Image: Wikimedia

On the other hand, we do have records of gray wolves in Alaska during the Pleistocene. And at the northern extent of their range, gray wolves can get pretty darn big. “It’s common for body size to increase when you get into very cold environments,” Dundas said. “We’ve seen gray wolves in Alaska and Siberia that are larger than any dire wolf skeletons.”

As for whether a dire wolf could have been tamed? “We’ve got no evidence for domestication,” Dundas said. “We know that dire wolves co-occurred with humans, so it’s a fascinating question what it would have been like to have a run-in with one.”

To sum up, Westerosian direwolves sound a lot more like large, Siberian or Alaskan gray wolves than their Pleistocene namesake. While the decision cast gray wolves on screen was clearly borne of necessity, it serendipitously makes the most scientific sense.

Manticores

In Game of Thrones, death can come in all shapes and sizes. One of my favorite underrated fantasy creatures is the manticore, a scorpion-like arthropod that lives on remote tropical islands in the Jade Sea, thousands of miles east of Westeros. Manticores are prized for their venom, a few drops of which can stop a grown man’s heart. Before Ser Gregor Clegane crushes Oberyn Martell’s head in Season 4, Martell manages to stab him with a venom-coated spear, leaving the knight on the brink of death.

Artist’s rendition of a manticore. Image: Max Berman/HBO.

Long before manticores were prized by assassins and alchemists, they lived happily in faraway jungles, feasting on smaller prey and growing as big as lobsters. To learn what their lives are like, I spoke to Lorenzo Prendini, a scorpion biologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The biggest baddest scorpions

There are nearly 2,000 known species of scorpions, and they’re found all over the planet. But based on the manticore’s size and habitat, there are only a few possible Earthly comparisons.

“The closest thing you’re going to get in the real world is either the emperor scorpion in tropical West Africa, or the giant forest scorpions in Southeast Asia and India,” Prendini said.

The emperor scorpion, one of the largest scorpions on the planet. Image: Wikimedia

The emperor scorpion, Pandinus imperator, and the giant forest scorpions belonging to the genus Heterometrus, are among the largest predatory arthropods in the world, with adults averaging 8 to 9 inches in length. Unlike with most other arthropods, these scorpions are what biologists call K-selectedorganisms, meaning they’ve chosen fewer offspring and longer lives over lots and lots of babies. A brood of emperor scorpions may include 20 to 30 babies max, and females invest an unusual amount of time and energy caring for their young. It takes a long time for emperor and giant forest scorpions to reach sexual maturity, and both types can live for more than thirty years.

Unlike desert scorpions, tropical scorpions can’t tolerate drought at all. Their heavy, wax-coated battle armor is built to retain moisture, and they stay cool by spending nearly all of their time in underground burrows coming out only at night to snag prey.

“These guys are extremely sensitive to their prey,” Prendini told me. “They can detect the subtle air current changes and the vibrations of insects half a meter away. When they sense prey they dash out of their burrow lightning speed, grab the animal and pull it back as quick as they can.”

In many respects, the lives of manticores are probably similar to those of other tropical scorpions. But there’s one very important difference between manticores and Earthly scorpions: their choice of weapon.

“On the whole, tropical scorpions don’t really rely on venom because they have such powerful claws,” Prendini told me. “Typically they’ll grab their prey and just start ripping it apart. Venom is costly, so they don’t waste it.”

When tropical scorpions do resort to venom, it’s usually to paralyze a panicked animal before they dismember it, or as defense against other predators. (Mongooses, owls, and certain lizards eat tropical scorpions, which, Prendini notes, are a great source of protein.) But the venom isn’t deadly.

“It’s pretty similar to a bee or a wasp sting,” Prendini said. “It’ll hurt quite a bit, but it won’t kill you.”

The Deathstalker, one of the most venomous scorpions in the world. Image: Wikimedia

Manticores, on the other hand, don’t possess fighting claws at all, so we’ve got to assume venom is their primary weapon, both for defense and hunting. This makes the manticore a bit of an outlier among scorpions: typically, as size increases, these creatures trade venom for muscle.

Indeed, the most toxic scorpions in the world are all rather puny. The Indian red scorpion, whose sting can send an adult human into cardiac arrest, tops out at about 3.5 inches length, while the Deathstalker, whose venom is a potent neurotoxin, rarely exceeds 2 inches.

Still, toxicity doesn’t necessarily relate to size—it’s a function of the many selective pressures of an organism’s environment. Perhaps, for the manticore, venom is a more effective predator deterrent than big, meaty claws. Or maybe manticores are locked in an toxic evolutionary arms race with competing species.

We can’t know for sure without more information. But whatever circumstances have produced this toxic fighter, it’s clear that the Jade Islands deserve a scientific expedition.

Lizard Lions

They don’t get as nearly as much attention as dragons, but there’s another fearsomely large reptilian predator prowling the backwaters of Westeros: the Lizard-Lion, sigil of House Reed. As far as we know, lizard-lions are found only in the bogs and swamps of the Neck, a region that divides the North from the rest of the Seven Kingdoms.

Image: Game of Thrones Wiki

Lizard-lions are crocodilian animals, and from the sparse descriptions found in the books, they behave much like their real-world counterparts, lying in wait to ambush prey like floating logs. It’s said that lizard-lions can grow to the size of actual lions and will viciously attacking unwary men who wander through the marshes.

Here’s one of the few descriptions of lizard-lions, from A Song of Ice and Fires:

Sansa shuddered. They had been twelve days crossing the Neck, rumbling down a crooked causeway through an endless black bog, and she hated every moment of it. The air had been damp and clammy....dense thickets of half drowned trees pressed close around them, branches dripping with the curtains of pale fungus. Huge flowers bloomed in the mud and floated on pools of stagnant water, but if you were stupid enough to leave the causeway and pluck them, there were quicksands waiting to suck you down, and snakes watching from the trees, and lizard-lions floating half submerged beneath the water, like black logs with eyes and teeth.

The Westerosian alligators?

Based on descriptions in the books, lizard-lions probably fall within the order Crocodilia, the taxonomic group comprising crocs, alligators and caimans. On Earth, these large, predatory reptiles are solitary creatures, normally sedentary but capable of swimming quickly and even galloping over land for short bursts to catch prey.

Their northerly distribution leads me to suspect lizard-lions are the Westerosian alligators. There are two species of alligators alive today on Earth: the American alligator, which can weigh up to 1,000 pounds, and the Chinese alligator, a smaller, critically endangered species restricted to the Yangtze river in China.

Both species are more cold-tolerant than crocodiles, which inhabit tropical regions of South America, West Africa, Asia and Australia. Indeed, in The World of Ice and Fire, George R.R. Martin’s comprehensive history of the Seven Kingdoms, we learn that there are crocodiles in Sothoryos, the southernmost continent in the known world.

The saltwater crocodile, the largest living crocodilian in the world, maxing out at 4,400 pounds. Image: Mike / Flickr

As for their famed aggression in the series, it’s true that crocs and gators do attack humans. But not often.

“A croc or gator might attack you if you come to the waters edge and effectively act like their prey does, but you don’t seem them going around hunting down people,” said Emma Schachner, a vertebrate physiologist and alligator expert at Louisiana State University. “Usually, they’re pretty low key.”

And if raised in captivity, crocs can be downright tame. Who knows, maybe some brave men and women of the North tried to cajole the beasts into battle once upon a time, or hitch a ride through the swamps of the Neck on their scaly backs. Then again, if you fell off a lizard-lion’s back and got trapped in the Neck’s treacherous quicksand, it was probably game over.

Krakens

Krakens are giant sea monsters that skulk deep ocean basins in the world ofGame of Thrones. Like lizard-lions, there’s scant information to be found on these beasts in either the books or the TV series. But we can be fairly sure they’re cephalopods:

“Kraken: strong, as long as they’re in the sea. When you take them out of the water, no bones. They collapse under their proud weight, and slump into a heap of nothing. You’d think they’d know that.”

-Ramsay Snow , A Song of Ice and Fire

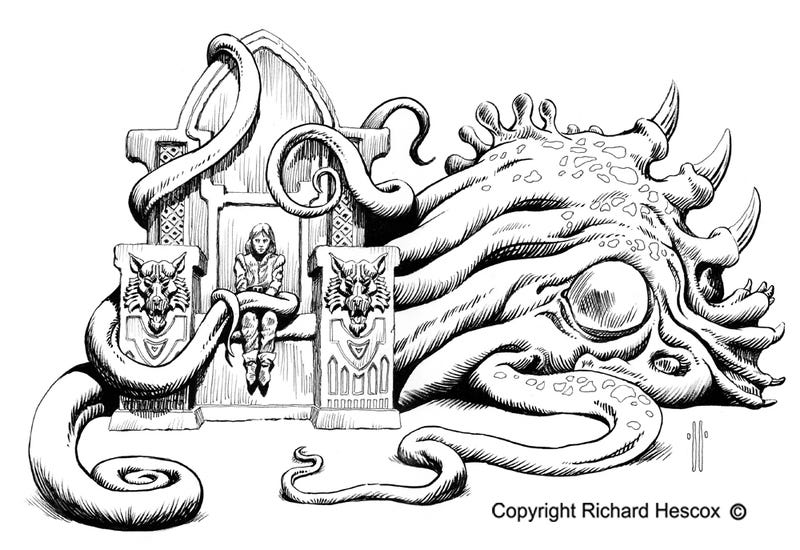

Image: Richard Hescox. Find more of his art on Facebook.

The most famous massive cephalopod on Earth—the giant squid—was also the stuff of legend far before humans ever confirmed its existence. Indeed, descriptions of a tentacled sea monster can be found in 13th century Icelandic sagas and old Norse scientific works. Kraken-like creatures have been with us in folklore for centuries, but the first clear photograph of a giant squid wasn’t captured until 2002.

The reason giant squids—and probably, the krakens of Game of Thrones—are so elusive has to do with their habitat. Giant squids are thought to inhabit every ocean on Earth, but only at depths below 300 meters. Like giant squids, krakens probably live in perpetual darkness, hunting fish and marine invertebrates, and fearing nothing save the occasional toothed whale encounter.

The one scientific issue I have with Krakens is their aggression toward humans. Krakens are said to viciously attack ships, and it’s been suggested that the scent of human blood draws them up from the depths of the ocean. If this were true, then krakens would either have to have a fantastic sense of smell, or live much closer to the surface than we imagined. Given that most deep sea creatures can’t survive depressurization, my money would be on the latter.

But again, these are unconfirmed rumors. If our own history is any indicator, it’ll be many centuries before the people of Westeros and Essos can say for sure whether krakens are anything more than the stuff of saltwater legend.

White Walkers

We can’t talk about the fantastical creatures of Westeros without mentioning White Walkers, the ice-blooded, humanoid race from the time of the First Men.

Image: Marc Simonetti

Also known as the Others, White Walkers first appeared roughly 8,000 years before the events of the series, descending from their arctic homelands during a brutal winter called the Long Night. They’re described in the books as tall, gaunt, pale humanoids, with brilliantly blue eyes. During their southern march, the White Walkers killed everything in their path without mercy or reason, reanimating human corpses as wights to join their frozen army. Eventually, the people of Westeros rallied together against the monsters, driving them back north and erecting The Wall to keep them there.

White Walkers possess superhuman strength, can freeze anything they touch, and are rumored to bring cold weather in their wake. But rather than just mindless killing machines, they seem to be an intelligent, humanoid species with a complex social structure, language, and stone-age technology. Could they, too, have a place in our world?

Sadly, I think the answer is no. Even if we allow White Walkers their magical ability to rise the dead, and their immunity to everything but dragonglass, we can’t get around the fact that biochemistry as we know it doesn’t work when you’re frozen.

There are a few microorganisms that can survive at subzero temperatures for long periods of time, by basically going into hibernation. But the idea of being metabolically active while frozen is incompatible with life as we know it. Every single biochemical process, from building new proteins to replicating DNA, is based on moving molecules around in a liquid media.

Sorry guys, but I think they’re just magical zombies.

After surveying just a few of the fearsome beasts of Game of Thrones, it’s hard to draw any overarching conclusions about the feasibility of their fantastical lives. Direwolves and lizard-lions seem like plausible creatures by Earthly standards, while dragons have some physiological issues, although if we grant them a magical heat source, those might be overcome. Manticores live in a jungle of alien horrors. Krakens are as mysterious as the giant squid, and White Walkers have no basis in Earthly biology whatsoever.

Of course, Game of Thrones is fiction, and part of the fun is that our rules don’t have to apply. Even if none of these creatures have a place in our world, at least they’re all appropriately terrifying for the violent fantasy realm they inhabit.

Sources: http://gizmodo.com/a-scientific-guide-to-the-fantastical-predators-in-game-1699034796?rev=1461364605164

You have the right to stay anonymous in your comments, share at your own discretion.